On 9th December 2016 I was honoured to introduce two films hosted by Transcreen at the International Queer and Migrant Film Festival in Amsterdam, ‘I am Bonnie’ (India, 2015, 45 min), directed by Sourabh Dutta, Farha Khatun, Satarupa Santra, and ‘Transindia’ (India, 2015, 30 min), directed by Meera Darji.

Watch me speak about migration, intersections and decolonisation here, or read the transcript below.

Thank you IQMF and Transcreen. Thank you Maik and Karola for bringing me here. I found myself asking, why am I here? I’m not Indian. I’m not a film maker. So why am I here? The answer is simply that my story is not one that is told.

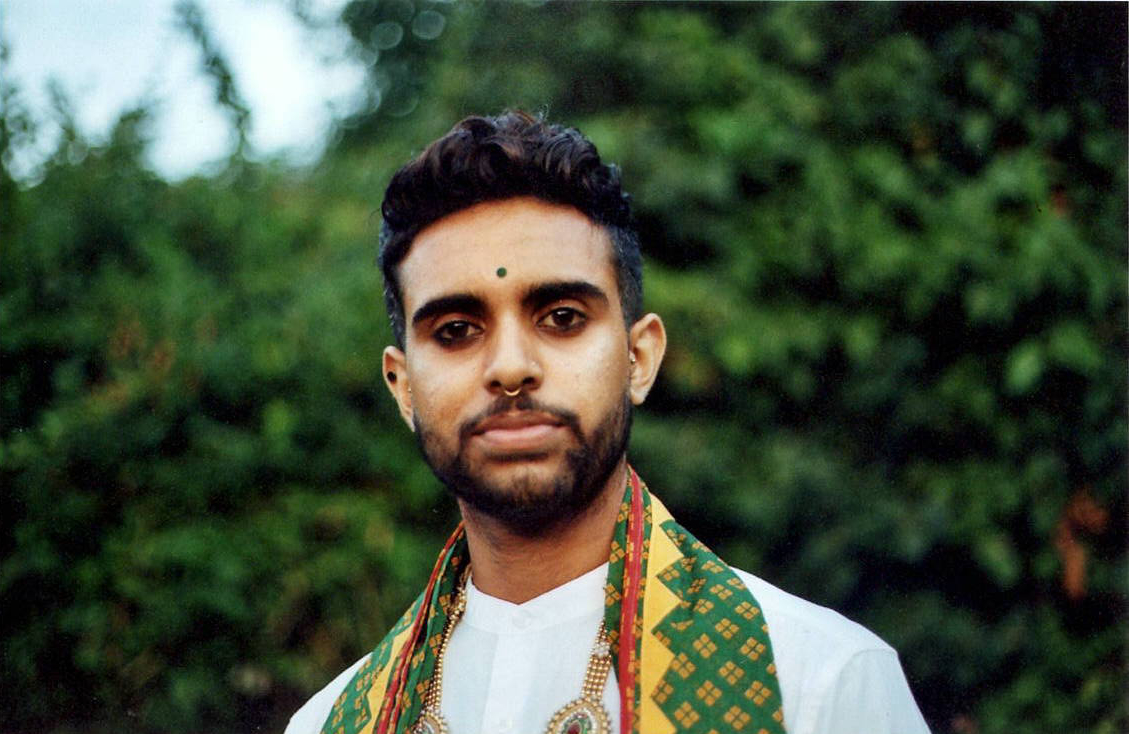

I’m trans. I’m queer. I’m Pakistani. My story isn’t seen. It doesn’t want to be seen. Much like ‘TransIndia’ and ‘I am Bonnie,’ our narratives are based on the delicate intersection of our identities. Our race. Our gender. Our faith. To survive on these intersections maybe surprising shocking. But for us, it’s natural, it’s absolutely necessary.

There was a time when I believed I couldn’t survive on these intersections. Once upon a time I made myself choose and forced myself to hide from myself. I forced myself to pick an intersection just so I could see myself reflected in the outside world. But that came at a price. I could chose to be brown and abandon my queerness. Or I could choose to be queer. But I’d adopt whiteness.

I talk about it now with awareness and a level of self-reflection. But for the most part of my life I ahd no idea I was choosing. I just felt: this is the only way. But there was one shaking moment when I realised it wasn’t the only way. And I knew it wasn’t the right way.

The day I came out as trans was the same day I came out as brown. It sounds silly, I know. I’d been talking about gender for a while, so it was a process I came to terms with. With my colour, well, I just hadn’t ever realised I wasn’t white. I was living in a white town with white friends and a white partner. All the conversations I had were with white people and were about white experiences. Being queer was synonymous with being white. I removed the hair off my upper lip and stomach in secret. I kept my desi family and their accents private. I drew white lines and white lies between me and my roots. I know that hurt my family, not being queer, but being white. When I came out as trans, I had my eyes open to a world, an identity and a body I would be migrating into. I understood what gender really meant, and saw what femininity looked like, what masculinity I desired… and when I looked within myself, I saw I would never fit these moulds.

My femininity is brown and hairy, undesirable. My masculinity is brown and threatening. My experiences of gender are racialised. I can’t separate them.

It was painful coming out as brown. I cried when I realised the colour on my hands and body was brown and was never going to change. Whiteness, white queer and trans people could no longer be my point of reference. There was nothing out there that told me who I was, was okay. No one existed. And I felt like I shouldn’t exist. This is when living on the intersections becomes surviving on the intersections.

I stopped letting myself be defined by just one part of me. And that’s what intersectionality did for me. It validated me, all parts of me. The word and theory of ‘intersectionality’ was new to me, but the expreince was familier; and I think that’s what intersectionality is: it’s where parts of our identity merge, the parts that face oppression, that feel hurt but also the parts that hold power. It allows us to identify our privileges as well as name our injustices.

Because I can’t choose which identity, which part of me comes first.

Here in the West, I’m brown first.

Back in Pakistan, I’m queer first.

And in America, I’m Muslim first.

As we move through communities and migrate through countries, our identities move and migrate too. Being forced to choose only tells us that whatever ‘minority’ we are, we;re never going to be enough.

We live under set structures that define and dictate norms and expectations. These structures are built on historic and institutional power and built off oppression. These structures are patriarchal, these structures are colonial.

When these structures produce gender norms, beauty standards, and language, we see the true power of whiteness. We see how being beautiful is being white. We see transgender identity as colonised. As QTIPOC we are working towards western liberation models. Where our freedom is gay marriage. The right to have children. We as QTIPOC are following white LGBT narratives. Where coming out is the only way to show you’re proud. I’m not saying these things are wrong. They work for us. But these aren’t our only ways to be proud. To be liberated.

Being trans is still seen as a western ideology, as if it was invented in the west. As if we weren’t being trans before colonialisation. As if we didn’t have our own words to describe ourselves. I guess ‘trans’ in that respect is a white invention.

Because what trans looks like in my country goes beyond and before that. The country I live in now, colonised the countries of my mother, my father, my ancestors, and imposed laws that ostracised trans people, the hijra and khwaja sera community. The British Empire is responsible for the persecution of hijra and khwaja sera people, responsible for the homophobia and transphobia that so many Westerners see synonymous with Muslims and desi people. And at the same time, the U is waving a rainbow flag and leading the way for trans and LGBT rights across Europe and the rest of the world, telling us this is how it’s done. This is how to liberate yourselves. The truth is, any conversation on homophobia and transphobia needs to include a dialogue on colonialisation. The truth is any examination of my own gender and queerness is inherently about decolonisation. My journey is of reclamation, my transition is a migration. Migrating away from the narratives I’m told I need to follow to exist, out of the white default constructs of gender I’ve been imprisoned in.

We are migrants forced to leave our countries.

We are migrants within our own countries, when communities force us to leave.

We are migrants force to leave our too brown, too queer bodies.

Our search is ongoing.

Our gender is always shifting.

Our home is never still.

Yes our migration is painful.

But if intersectionality is my decolonial tool, then I can take my first step in migration as decolonisation. My first step in migration will be reclamation.

And then one day, I’m sure, I will find my way back home.