Visit Kicking the Kyriarchy for all episodes and subscribe to their podcast.

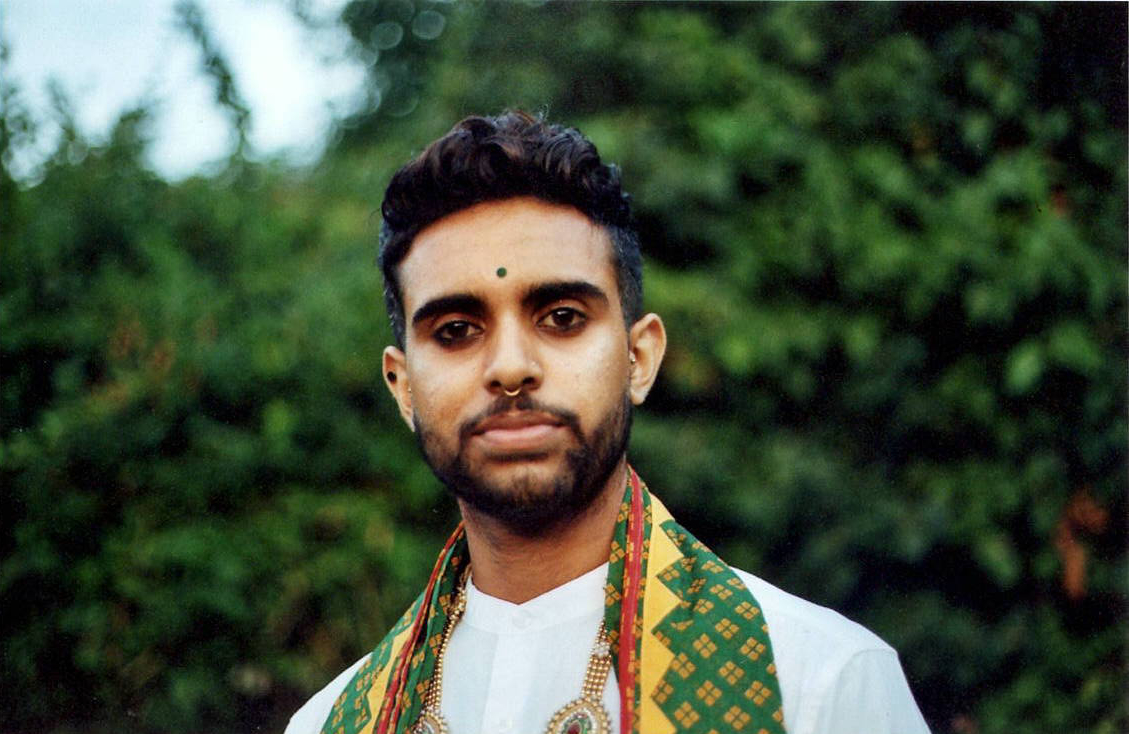

Sabah Choudrey: Hello my name is Sabah. I am hairy brown, queer, trans person, able-bodied, Pakistani. I’m Muslim. I’m also a trans youth worker and I like writing.

Kicking The Kyriarchy: Thank you so, so much for giving up your time for a phone interview, we really appreciate it.

SC: That’s alright!

KTK: If you’re comfortable with it, could you maybe describe to us, or define, what is trans?

SC: Yeah, so I was actually just doing a LGBT training aimed at teachers today so I’m in this zone of defining trans! So yeah, trans is an umbrella term, it means basically someone who doesn’t identify with the gender that they were assigned at birth which is usually either male or female. It could be about someone’s gender expression or gender identity. Sometimes people make up gender identities and that’s really awesome. Sometimes the gender identities are cultural, like specific to different parts of the world and different communities. I guess what trans means to me is just not being either male or female or a man or a woman. To me, being trans means, like, my body is gender non-conforming and my gender expression is fluid and my gender identity is really personal um, and private almost. To me being trans is being a gender-fuck and being confusing and making people question, screwing with people’s ideas of binary genders by existing I suppose, and having a really confusing body type or appearance.

KTK: You kinda started talking about what being trans meant to you, would you be able to tell us a bit about what your journey has been so far?

SC: I think a lot of people expect me to have set dates and times and moments where like, I came out as trans or I transitioned or I, you know, did xyz milestone in my trans journey, and like [sigh] I just don’t really remember because it doesn’t really matter that much to me, those kind of steps, or how long it’s been since I started using different pronouns or – and then I guess that’s related to how little medical transition and the medical intervention has played a part in my own gender journey. Yeah.

KTK: Being trans isn’t always about medical transitioning but for some people it is, is that what you mean by that?

SC: Yeah so the mainstream narrative of being trans is very medicalised and its very much like: you are transitioning from one gender to another with these hormones and this surgery and that’s that. But um, actually the medical part of my transition was just so unimportant and it was all the other stuff that came along with it that I feel is far more exciting and interesting, like the social aspect – not even like ‘transitioning’ in inverted commas but just moving between a different mindset or occupying different spaces, as someone who is presenting differently to what they’re expected to present as.

KTK: Okay, so when you look at the media for maybe the past like five years, and you’ve seen an increase in the number of celebrities coming out as trans. And to some extent this has been a good thing because it means that trans issues are being brought to the forefront, but what are your thoughts on this? I mean, do you think that these people are representing you?

SC: Yeah… Visibility is a tricky one. It was only recently that I allowed myself to sit on the fence about whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing. And I think a lot of that has come from my own journey I suppose, and um, searching for personal validation that ‘Oh, I can be a person of colour and I can be trans at the same time,’ and just because there isn’t anyone out there in the media who looks like me, doesn’t mean I can’t still exist. The other thing is just from working with so many trans young people, I can’t underestimate the power of visibility; it is so important that they see someone like them. I didn’t really feel like trans people in the media represented me. Um, when I started to accept that I might be trans, I don’t think there was any trans people in the media at all really, so there was definitely no representation in terms of like, trans people of colour or like South Asian queer people. So that was a lot of of why I started to put my own voice out there and started writing and started to get involved in like LGBT community groups and I guess, activism, and just setting up spaces. It was kind of like, ‘Fine, okay if there’s no representation of us in the media, but let’s just try and carve out a space where we could exist.’

KTK: Because I’m kind of like thinking of the people like, I mean it might be a bit cliché, but I’m thinking of people like Caitlyn Jenner.

SC: Yeah.

KTK: And how there is a lack of trans people of colour, you know, as somebody who has never had to struggle to see people that look like me in the media I’m wondering what that’s like.

SC: It is interesting, it is just a privilege just being able to see yourself represented on the TV or in the magazine or on the news or something . Well not on the news because trans people of colour are represented on the news, we’re just like, tragedies. Yeah, when I think about trans representation now , I don’t really think about it as something for myself; I think about it as something that’s for trans youth who I support. It’s just more important for them I suppose, that they’re growing up in a world where people like Caitlyn Jenner are already out there, and there are trans storylines on the soaps and the TV that they’re watching and it’s there it’s already there and they’re not having to search out for it.

KTK: So young trans people today have more people to look up to.

SC: Yeah.

KTK: And they’re perhaps easier to find on the internet as well?

SC: Yeah totally. Online is that place to look for people who do occupy more than one identity, so like non-binary people of colour, trans people of faith, disabled trans people – everyone who hasn’t been given a platform yet I suppose. And it’s also easier to stay safe online. The price of visibility is that you’re not safe. But online you can kind of navigate that alright. And even if the representation in the mainstream doesn’t represent the trans young people, there will be conversations about why it doesn’t. They will be loud and that’s amazing. Because when I was younger, there was just no space to even have that conversation about why it’s important, it was just like, this doesn’t exist so that’s the end of that. It’s pretty powerful because it pushes them to be their own representation and be their own role models. Which is amazing

KTK: [chuckle] What kinds of stereotypes are there of trans people that perhaps aren’t helpful, particularly to cis people who haven’t really thought about it before?

SC: I have been thinking about trans people of faith and queer people of faith; there is just such a prejudice against the Muslim community for being transphobic and a stereotype that trans people can’t be religious as well. It really bothers me because it just means that there is less of a space where we can then exist. You know. If Muslims are seen as transphobic then we can’t be associated with Muslims, but if trans people are seen as people of no faith or atheist, then where do we go? It’s a real battle because as soon as people hear that I’m Muslim or I tell them that I’m Muslim, no matter how fleeting it is, if it’s just a comment suddenly it’s like, oh well, what does the Muslim community say, how can you be Muslim and trans, how like, all this other shit about how I’m probably not Muslim enough and am I really Muslim if I can do that – yeah it just becomes a battle and that just makes me not want to talk about being Muslim, which really pisses me off because I’ve been hiding that part of me for so long and hiding different parts of me for so long that why would I want to keep hiding. It’s just really frustrating. And in those moments I think that that visibility, like I’m in a position of privilege where I can be safe and visible and talk about my experiences and it’s more important that I say I’m Muslim and trans than I don’t say it. Does that make sense?

KTK: Yeah definitely.

SC: Like I can deal with ignorance and Islamophobia and homophobic comments. It’s more important that I’m there and saying I am both of these things, even if someone disagrees and thinks I’m deluded or a sin, at least I’ve said that I’m still here. People view being Muslim as a binary, in that either you’re a Muslim or you’re not, and the binary of being a Muslim is usually really like, quote, ‘traditional,’ ‘strict,’ ‘conservative,’ ‘practicing,’ whatever the fuck those words mean – it’s very that. Um, and you’re either that or you’re not. And there’s no room for it to be a personal thing, there’s no room for it to be a fluid thing, there’s no room to have doubt, there’s no room to be, to be like, in between. There’s no room to be like, a non-binary Muslim, [laughs] on that kind of spectrum and faith is a spectrum just like any other part – I think faith is a spectrum just like any other part of my identity. It’s just so frustrating that people can’t see that.

KTK: So, being a person of colour and being trans, that’s like two identities and being a person of colour is almost an identity that you don’t really have like much control over what people are seeing, whereas with trans, and I’m aware that this question might come across as potentially quite problematic, but with being trans it’s not necessarily a visible identity. So what’s that like, having identities like that – one that’s really visible and one that’s less so? Assuming that you, in inverted commas, ‘pass’ which I know is really problematic.

SC: So um-

KTK: -and happy to be called out on that.

SC: It’s okay, so understanding that my colour, my skin colour comes first, was really, really difficult and quite a painful thing to accept I suppose, because I was, I was out as a lesbian and I was in a really white LGBT community, all my friends were white, my partner was white, my housemates were white – I was in Brighton for fuck’s sake, it was super white. And it just never occurred to me that my skin colour was a colour I suppose, it didn’t even occur to me, and when I realised I’m always going to be brown and that is the first thing that people see, and then they see that I’m whatever, you know, visibly queer second, or a dyke second, then I don’t know, it just felt like I didn’t have control, but I guess that’s probably what it feels like when you don’t have power in those situations or when power is taken away from you. It’s really frustrating because feel like even now, I guess I’m not as visibly queer or um, I pass as a cis person. I have a cis-passing privilege which I don’t like but I have it so I have a choice now like to show or out myself.

KTK: So why do you chose to out yourself?

SC: Oh my god because I love it, I love being trans and I really love being queer and I want all parts of me to show at once and to be all of those things at once. I always felt like I was going to lose some kind of queer visibility if I started, you know, taking hormones or passing or, you know, just by dressing more masculine or differently. Having that choice is a massive privilege and um, unfortunately part of like, making that choice is a choice to be safe, and not a target.

KTK: What does passing mean to you and what kinds of privileges would I have that I would never have even thought about?

SC: Okay… So passing is the idea that a trans person will go undetected as the gender that they present as without people knowing that they’re trans or that they identified as a different gender or were assigned a different gender at birth. Passing is really validating for some trans people but it’s quite problematic because it implies that trans people need to look a certain way and the certain way is to look like a cis person. And I’m sure you know the pressures of what women should look like so for trans women to pass as women, it’s just like even more pressure to conform to sexist standards or um, behaviour or expressions or appearances.

KTK: So we’ve talked a little bit about visibility – why is it important to have a trans day of visibility?

SC: It’s important because seeing someone who is like me out there in the media being represented, being safe and uplifted tells me that people like me exist are happy and proud and it’s validating. But it’s very revealing who does get to be visible and who gets to choose to be visible. For me, visibility and safety go hand in hand and it might be up to trans people to be visible but it’s not up to us to be safe. We don’t determine how safe we are, it’s the rest of the, it’s the other people, it’s the people who oppress us, it’s the people who target us, it’s the people who have power over us.

KTK: Absolutely, and society as a whole. Which bring us onto what can we do as allies to trans people of colour and maybe trans people of faith?

SC: I think the moment you start talking or learning about trans people, start learning about people of colour and people of faith at the same time. Because trans people of colour are a part of the trans community; we will exist within it and we will exist outside of it. Don’t just expect to just Google ‘trans’ and expect brown and black faces to show up because we probably won’t. Do your homework I suppose. Listen to us, listen to our stories, find out what organisations support us, share our resources that are written by trans people of colour for trans people of colour, find a way to give us money or help support us to get funding because chances are we are underfunded. Just making sure you’re not learning about thing in isolation. I guess taking an intersectional approach to supporting trans people of colour in that way, and lastly just keep going; the moment we say we’re done learning is the moment we miss something and our privilege blinds us. Being honest about your privilege, because it’s not a bad thing, like, everyone has privilege, being aware of it is the first step to being able to redistribute that power. Being an ally means giving up that power essentially, to me.

KTK: What advice or words of wisdom do you have for other trans people of colour and maybe other trans people of faith? And also what projects are you working on so that we can provide a platform for those of our listeners who can help you out and follow you and see what you’re up to.

SC: I guess a message that I want to give to people who are coming to terms with being Muslim and LGBT is that it’s completely our choice and I know people use Islam against us and there’s a chapter in the Quran that says: ‘God does not burden any human being with more than he has given him and it may well be that god will grant after hardship, ease.’ To me it just reminds me that, us coming to terms with being Muslim and trans, or Muslim and queer, is never going to be our only trial and nor is it going to be only our trial either. Like just as we are tested deeply and personally about what our faith looks like as queer and trans Muslims, those around us, like our family and straight and cis Muslims in the rest of the community are tested on what their own faith looks like and how accepting and loving it can be for queer and trans Muslims as well.

KTK: That was really nice.

SC: Is that alright?

KTK: Yeah that was really good. I like the quote from the Quran I’ve never been quoted it before. So what projects are you working on?

SC: At the moment I’m working with Metro doing their trans youth support work ,which is a new project, also working as a trans youth support worker with a transgender charity called Gendered Intelligence, and running a group for trans people of colour. I’ve also started getting involved with Inclusive Mosque Initiative who are LGBT inclusive, feminist, Muslim organisation who hold fortnightly Jummah prayers which don’t segregate men and women for prayer, just a really inclusive space. I’m kind of taking a back seat from public speaking and writing for the time being but you can keep in touch with me on Facebook.com/SabahChoudrey or find me on Twitter @SabahChoudrey.